The Necronomicon

The Necronomicon is a fictional grimoire (textbook of magic) created by horror writer H.P. Lovecraft. The book contains powerful chants and rituals that can summon otherworldly beings and unleash unspeakable horrors upon the world. It has become a staple of Lovecraftian lore, with many fans of the horror genre intrigued by the mysterious and ominous reputation of the Necronomicon.

One particularly significant date associated with the Necronomicon is September 13th. This date is often considered a day of reverence for the book, with some believing that the energies surrounding the Necronomicon were incredibly potent on that day. Some even claim that September 13th is when the book's dark powers can be harnessed and used to achieve one's desires.

It's crucial to remember that the Necronomicon is purely a work of fiction. Lovecraft himself stated that the book was a product of his imagination and not based on real occult practices. This reassurance should not diminish the allure of the Necronomicon and its mysteries, which continue to captivate audiences today.

For those eager to explore the world of the Necronomicon, there is a wealth of books, movies, and games that draw inspiration from Lovecraft's work. The Necronomicon's influence transcends literature, permeating tabletop role-playing games, video games, and even music, demonstrating its profound impact across a broad spectrum of media.

Gromoires - The “Real” Deal!

Reflecting on the Necronomicon automatically leads to considering other Grimoires - and yes, such magical textbooks do exist!

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), where they were found inscribed on cuneiform clay tablets that archaeologists excavated from the city of Uruk and dated to between the 5th and 4th centuries BC.

The ancient Egyptians also employed magical incantations, which were found inscribed on amulets and other items. The Egyptian magical system, known as heka, was greatly altered and expanded after the Macedonians, led by Alexander the Great, invaded Egypt in 332 BC.

The ancient Greeks and Romans believed that the Persians invented books on magic. The 1st-century AD writer Pliny the Elder stated that magic had been first discovered by the ancient philosopher Zoroaster around 647 BC but that it was only written down in the 5th century BC by the magician Osthanes. Modern historians do not support his claims, however.

The Jewish people were often viewed as knowledgeable in magic, which, according to legend, they had learned from Moses, who had learned it in Egypt. Among many ancient writers, Moses was seen as an Egyptian rather than a Jew. Two manuscripts likely dating to the 4th century, both of which purport to be the legendary eighth Book of Moses (the first five being the initial books in the Biblical Old Testament), present him as a polytheist who explained how to conjure gods and subdue demons

Some (in) famous Grimoires

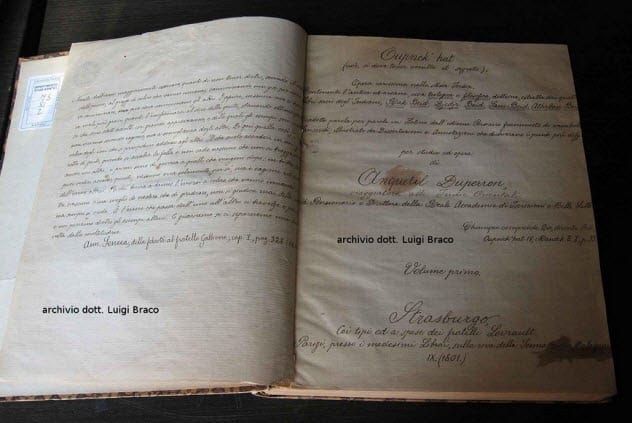

The Oupnekhat

The Oupnekhat is a Persian work possibly derived from a 19th-century German translation of an earlier Latin edition, likely a revision of the Hindu Upanishads. The Upanishads are several books containing esoteric wisdom concerning Hindu metaphysics, which can be compared to other Hindu treatises and scriptures.

The Oupnekhat aims to aid the production of wise visions. It details rituals to become one with the great being, presumably the Brahma (one of the three supreme gods in Hinduism). The practitioner tries to become the Brahma-Atma, the divine spirit, which is a lovely goal.

The Sworn Book of Honorius

The Sworn Book of Honorius is purportedly one of the oldest medieval grimoires, having been mentioned in written records as early as the 13th century. The prologue claims that the text was compiled to preserve the core teachings of sacred magic in the face of persecution, which is somewhat paradoxical given the heavy restrictions that the text lays out against duplication and circulation.

The 93 chapters of the book cover everything from catching thieves to saving a few souls from purgatory and detailed instructions on conjuring and commanding spirits - a staple for any respectable grimoire.

Among many other things, the user can view purgatory, know the time of one’s death, bury empires, become invisible, and obtain knowledge of all the sciences.

The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage

The Book of Abramelin is a long letter addressed to the author’s son. The author explains magical apparatuses and rituals concerning the invocation of spirits.

The text initially spends several chapters detailing the myth of how the author came upon this knowledge and then uses several more to discuss the preparations for the rituals. Once the terms and conditions are out of the way, the user can perform the ceremony to call about spirits who perform a feat or two for their summoner.

These feats include but are not limited to walking on water, reviving a dead body, causing an army to appear, and transforming men into animals and vice versa.

The Munich Manual of Demonic Magic

The Munich Manual of Demonic Magic, a 15th-century grimoire, breaks tradition by concerning itself solely with the evocation of demonic spirits, ignoring angel folklore and less eerie spirits.

The book classifies its experiments as illusory, psychological, or divinatory.

The illusory experiments can make a thing appear as something it is not, allowing the user to become invisible or make the dead seem alive if they wish. The psychological experiments grant the user influence over the minds and wills of others. And the divinatory experiments involve the cooperation of demons to know all things past, present, and future.

The Clavicle of Solomon

The Clavicle of Solomon, revealed by Ptolomy the Grecian, represents one of the earliest manuscripts of the infamous Key of Solomon, the most influential grimoire.

The book details some broadly named experiments of invisibility, love, envy and destruction, mocking and laughing, and grace and impetration (obtaining by petition or plea).

The Emerald Tablet

The Emerald Tablet is ancient enough that even its original language is debatable. The oldest documented source for the text is an Arabic work written in the eighth century.

Some myths attribute the tablet to Hermes Trismegistus, the father of Western alchemy. Others attribute it to the third son of Adam and Eve, and still more attribute it to the fabled city of Atlantis.

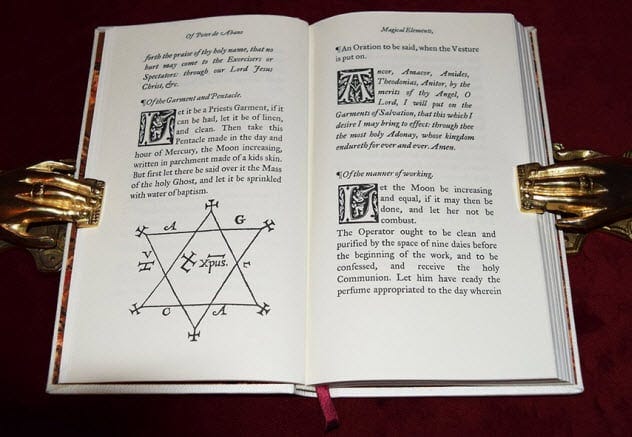

The Heptameron

The Heptameron is a guide to angel magic that dates to medieval times, if not further back. It has been attributed, probably falsely, to Peter de Abano, a 13th-century physician famously reputed to be a magician.

The text concerns itself with rites to conjure angels for each seven days of the week. It analyses the nature of each angel and the services they can provide to the practitioner. Some highlights include the angels of Tuesday, who can provide an army of 2,000, and the angels of Wednesday, who can reveal all earthly things—past, present, or future.

De Nigromancia

De Nigromancia is a 16th-century Latin manuscript attributed falsely to the famous English scientist Roger Bacon. It is among several occult manuscripts ascribed to Bacon, who openly opposed false claims of authorship and felt that books attributed to the biblical King Solomon should have been banned by law.

The title refers to necromancy, the branch of magic concerned with raising and controlling the dead. The book offers instruction on occult practices following from necromancy. The text focuses on ceremonial magic, specifically a branch known as Goetia, for summoning less amiable spirits, such as wraiths. Several illustrations of sigils, pentagrams, and seals are provided to aid the process.

The Picatrix

The Picatrix is a 400-page document, originally written in Arabic, about celestial magic. Its style of writing reflects that of a student notebook, so some historians ascribe it to an unknown apprentice of a Middle Eastern magic school.

The text's central theme is obtaining and channelling energy from the planets of the cosmos. The intention is for the practitioner to harness energy from the cosmos and use it to subjugate circumstances to his will. The text borrows from numerology and astrology to guide the rituals needed for such magic.

Unlike many Western grimoires, the book also includes bizarre recipes to be prepared for certain spells. Ingredients for these recipes include all manner of bodily fluids and psychoactive plants. The latter may be responsible for some of the grimoire’s supposed authoritativeness.

The Grand Grimoire

Considered one of the most famous and outrageous grimoires of black magic, The Grand Grimoire is associated with some truly outlandish myths. The authoritative manuscript is allegedly kept in the Vatican’s secret archives, and the text is said to be fire-resistant.

While it cannot be dated much sooner than the early 1800s, it is said to have been written by King Solomon himself. More so, the English translation of the book by A.E. Waite omits a significant portion of the text, apparently in an attempt to render the remaining translation useless, if not destructive, to the practitioner.

The Grand Grimoire's contents justify all the superstition surrounding it. The book's defining ceremony focuses on conjuring and making a pact with the devil. Once the pact is made, the conjurer can have unbridled power.

There are other instructions on making a Philosopher’s Stone, enchanting firearms, making oneself invisible, and that lot. But it seems pretty diminutive as a follow-up to summoning Lucifer. Perhaps the Vatican allegedly made the right move.

The September Moot

Grimoires will be the discussion point at September's online Moot. If you subscribe to this newsletter, you will automatically get an invite to the Zoom session

Alan /|\

Have you visited my NEW website and the blog there?