Macumba, Hoodoo and Voodoo:

A Deep Dive into Afro-Diasporic Spiritual Practices

Various cultural traditions have shaped the spiritual lives of millions across the globe, particularly those emerging from African heritage. Macumba, Hoodoo, and Voodoo represent vibrant expressions of Afro-Diasporic spirituality, weaving together elements of African religious practices, Indigenous beliefs, and European influences. While often conflated, these traditions possess distinct identities and practices that merit exploration.

Voodoo: Roots and Rituals

Voodoo, primarily associated with the African diaspora in Haiti, is a syncretic religion that blends elements of West African spiritual traditions with Catholicism and indigenous Taíno beliefs. Voodoo practitioners, known as Vodouists, believe in a supreme god (Bondyé). Still, they also revere a pantheon of spirits known as Loa (or Lwa), each governing different aspects of life. Rituals often involve music, dance, and the invocation of these spirits to achieve healing, protection, and guidance.

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Voodoo is its communal nature. Ceremonies are typically held in large gatherings called "services," where practitioners come together to celebrate, honour, and seek assistance from the spirits. Contrary to popular sensationalism, Voodoo emphasises harmony, respect for nature, and the interconnectedness of all life.

Hoodoo: A Practical Tradition

Hoodoo, often called "rootwork," is a folk spiritual practice that originated among African Americans in the Southern United States. Unlike Voodoo, Hoodoo is not an organised religion but a system of spiritual practices focused on achieving practical results in everyday life. Its roots lie in African traditions, Native American practices, and European folk magic, leading to a rich tapestry of rituals, spells, and herbal remedies.

Hoodoo practitioners often use herbs, candles, and personal belongings to create powerful charms and spells that promote love, protection, luck, and success. A key component of Hoodoo is its focus on the individual's connection to the spiritual realm, allowing practitioners to adapt and tailor practices based on their unique needs and circumstances.

Importantly, Hoodoo embodies a deep sense of community and family heritage, with many practitioners relying on the wisdom passed down through generations. This emphasis on ancestry and roots connects Hoodoo deeply to the African American experience, serving as a means of cultural resilience and identity in the face of historical oppression.

Macumba: Afro-Brazilian Spirituality

Macumba is often an umbrella term encompassing various Afro-Brazilian religions, including Candomblé and Umbanda, which blend African traditions, Catholicism, and indigenous beliefs. Originating from enslaved Africans brought to Brazil, Macumba reflects the syncretism characterising many Afro-Diasporic religions. Practitioners of Macumba honour orixás (deities) that represent natural forces and ancestral spirits, engaging in rituals intended for healing, divination, and community support.

Macumba rituals are marked by vibrant music, dance, and offerings, with ceremonies often conducted in public spaces or sacred grounds known as terreiros. Each orixá possesses distinct attributes, colours, and rituals; practitioners work with these spirits to navigate life's challenges. Macumba has faced stigma and misconceptions, partly due to its portrayal in popular media, yet its foundational principles emphasise love, harmony, and celebrating life.

Interconnections and Distinctions

While Macumba, Hoodoo, and Voodoo share common African roots and demonstrate the resilience of cultural expression amidst adversity, they serve different functions within their respective communities. Voodoo emphasises communal rituals and a pantheon of spirits, deeply rooted in the cultural context of Haiti. Conversely, Hoodoo is a more individualised practice focused on practical results and personal empowerment. Macumba embodies the vibrant cultural synthesis found in Brazil, highlighting the diversity within Afro-Brazilian spirituality and celebrating diverse influences.

Cultural Misconceptions and Modern Expressions

Misconceptions, stereotypes, and sensationalised portrayals have often marred the global perception of these spiritual traditions. Voodoo is frequently depicted as dark and malevolent in popular culture, overshadowing its rich history and the depth of its practices centred on community well-being.

Hoodoo faces similar challenges, often misunderstood as mere superstition rather than a legitimate spiritual practice with historical roots. Macumba, too, has been subject to misinterpretation, frequently reduced to caricatures that ignore its complexity and significance.

In recent years, interest in these traditions has been resurgent, driven by a desire to reclaim cultural heritage and foster understanding. Practitioners of Macumba, Hoodoo, and Voodoo have begun to share their stories, educate others, and highlight the positive aspects of their spiritual practices. This cultural renaissance emphasises the importance of community, identity, and resilience in facing ongoing challenges.

As modern practitioners seek to rectify historical inaccuracies and reclaim their narratives, social media platforms and community gatherings have become vital spaces for sharing knowledge and fostering connections. Online forums, workshops, and cultural events allow for dialogue that transcends geographical boundaries, leading to a broader acknowledgement of the significance of these spiritual traditions in contemporary society.

In these contexts, practitioners emphasise the importance of education and representation. They challenge the stereotypes perpetuated by mainstream media and invite others to engage with their practices respectfully and informatively. These efforts serve to celebrate their heritage and create an inclusive dialogue that promotes understanding and respect for diverse cultural expressions.

Cultural appropriation presents another challenge for Afro-Diasporic spiritual practices. As aspects of Voodoo, Hoodoo, and Macumba gain popularity in various subcultures, practitioners advocate for the ethical engagement with their traditions. They emphasise the need for those outside the traditions to approach them humbly, recognising the historical context and the cultural significance embedded in these practices. This call for respect and authenticity is crucial as these spiritual paths continue to evolve in the modern world.

Future Directions: Bridging Tradition and Modernity

Looking to the future, there is a growing awareness of the need to preserve and innovate within these spiritual traditions. Many practitioners integrate modern tools and ideas while remaining deeply rooted in their ancestral practices. This dynamic blend of old and new revitalises these traditions and allows for their continued relevance in a rapidly changing world.

Afro-Diasporic spiritual practices are finding new expressions in literature, music, and visual arts through collaboration with scholars, artists, and activists. These collaborations aim to inspire future generations to engage with their cultural heritage, fostering a sense of pride and identity. Furthermore, interfaith dialogue and cooperation with other spiritual communities can promote mutual understanding and respect, emphasising the universal themes of love, healing, and community within diverse spiritual practices.

The Enduring Legacy of Macumba, Hoodoo, and Voodoo

Macumba, Hoodoo, and Voodoo represent powerful testaments to the resilience of Afro-Diasporic cultures and spiritualities. They encapsulate centuries of history, struggle, and triumph, continuing to serve as sources of strength and identity for countless individuals today. As these traditions evolve and adapt, they remain vital expressions of cultural heritage, community, and spirituality.

Appreciating the depth and richness of Macumba, Hoodoo, and Voodoo reminds us of the importance of recognising and respecting the diversity within African diasporic traditions. Rather than allowing fear and misunderstanding to dominate perceptions, embracing education and open dialogue can foster appreciation for these spiritual practices.

As society grapples with issues of race, identity, and cultural appropriation, the voices of practitioners and scholars become increasingly important. Their narratives challenge misconceptions and highlight the profound connections people can share through spirituality, regardless of their backgrounds.

The enduring legacy of these traditions lies in their historical roots and their ability to adapt and thrive in contemporary contexts. They embody a sense of community and continuity, bridging the gap between past and present. Voodoo, Hoodoo, and Macumba are not relics of history; they are living traditions that continue to evolve, drawing on the wisdom of ancestors while addressing the challenges of modern life.

In conclusion, Macumba, Hoodoo, and Voodoo invite us to celebrate their unique identities and engage deeply with their teachings. They remind us of the universal search for healing, connection, and understanding in our human experience. By honouring these traditions and their practitioners, we can contribute to a richer, more inclusive tapestry of cultural heritage that celebrates diversity and promotes unity. As we move forward, let us commit to fostering reciprocity and respect, allowing these powerful spiritual practices to illuminate the paths of many for generations to come.

Baron Samedi

Within the religion of Haitian Voodoo, the task is carried out by the Loa known as Baron Samedi. Loa are spirits in the African diasporic religion of Haitian Voodoo. Baron Samedi’s name, translated, means “Lord Saturday,” and he is the most recognisable of the Voodoo Loa.

This figure is potentially one of the few known by non-practitioners of Voodoo because the character featured on the James Bond film, Live and Let Die.

It’s fair to say that this film (Live and Let Die) popularised many of the stereotypes held in the West.

The use of Voodoo by the Drug Lord in this film echoes to some extent the real-life (mis)use of the religion by the Black Republic of Haiti’s Francois Duvalier - Papa Doc. He formally took the self-penned title of Incorruptible Leader of the Great Majority of the Haitian People, Renovator of the Republic, Chief of the Revolution and Spiritual Father of the Nation.

Duvalier’s regime began in 1957 and lasted longer than any other in Haiti's history. Of the 36 Presidents who preceded Papa Doc, 23 were either killed or overthrown. Bloodshed and violence became a way of life.

He maintained a personal army of 5,000 militiamen, including the dreaded Tontons Macoutes (Haitian Creole for “bogeymen”).

The Tontons, sunglasses-wearing thugs whose fanatical loyal ty to Duvalier was rewarded with virtual licenses to torture and kill, murdered thousands of their fellow Haitians. Often they slit the throats of their victims and left them tied to chairs or hanging in market places for days as “examples” of what could happen to anti Duvalierists.

Duvalier himself, aware of the incredible hold that voodoo has always had on a vast majority of Haitians, used it for his purposes. He carefully kept on good terms with the powerful houngans (voodoo priests) and bogors (sorcerers) revered and feared by the people, and indulged in, often led, voodoo rituals himself. Voodoo as a religion was used as an excuse for and a means of maintaining control and spreading fear.

Of course, this is not the first example of religion being skewed by dictators for their ends, and sadly, it won’t be the last. If you speak to the uninformed, however, the Bond film and Papa Doc’s dictatorship will be the immediate associations with the word Voodoo.

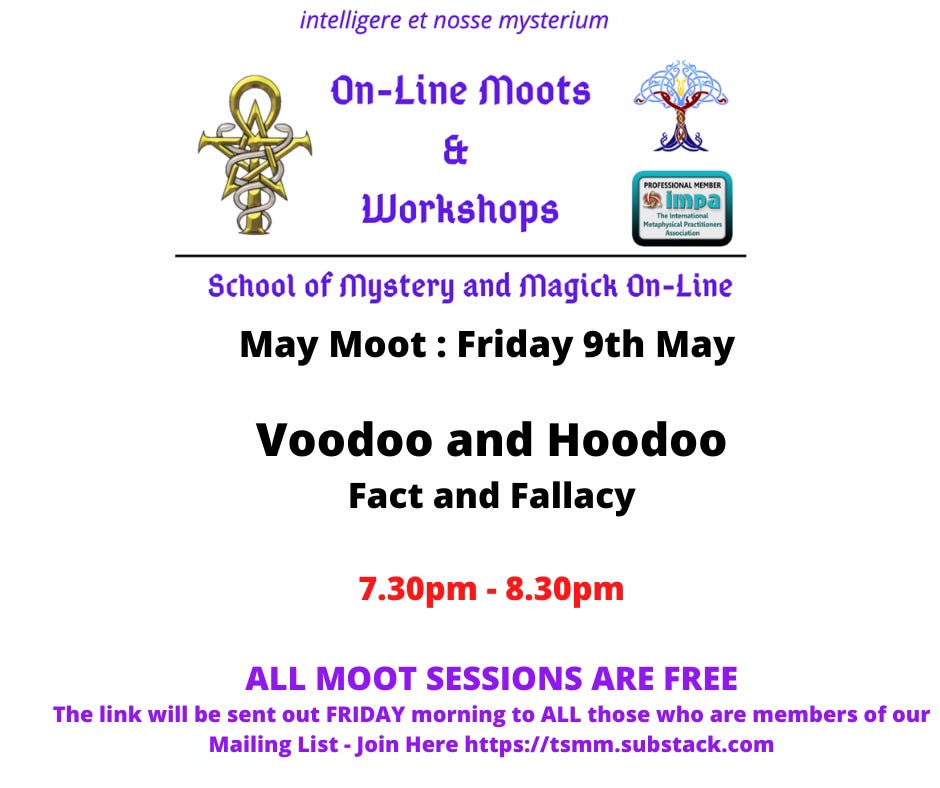

In this month's Moot, we’ll be dipping into the traditions of Voodoo, Hoodoo and Macumba. We’ll look a little bit deeper into the traditions of these practices and explore some of the myths around them. We’ll look at the idea of Zombies, Voodoo Dolls, and other ideas often misrepresented in popular culture.

Invitations will be sent out on Friday morning.

Alan /|\

Clear Mind is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free subscriber.

Have you seen:

Lessons in the Occult?

Tarot Academy?

Our Library of Moot Recordings?